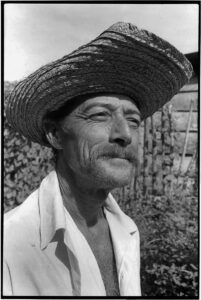

Many city-dwelling Cubans love to poke fun at Guajiros for their simple ways, but the truth is, I wish more Cubans were like them. In fact, I open this book with Guajiros like this man because they represent much of what I believe is best: they are proud of their Cuban heritage and are more family-focused, optimistic, and resourceful. In Guajiros, I also see my paternal grandfather, Miguelito from Charcas, Cienfuegos, who helped raise me as a Guajiro exile living in Hialeah.

Three things about my abuelo perfectly capture how Guajiro he was. First, he raised roosters, chickens, and other farm animals in his backyard until the day the City of Hialeah outlawed them and fined him. Second, he refused to learn to drive. And third, despite not driving, it was my father, uncle, aunts, or cousins’ daily responsibility to ensure abuelo always had a ride to tend to his animals on the farmland he rented. Even when abuelo had a mini-farm at home, he insisted on renting a farmland for his larger group of animals. For abuelo, being a Guajiro was not just a way of life—it was THE way of life.

Near the land this Guajiro tills with his hands lie the remains of my great-grandmother, Mercedes Gil, who lived to be 103, and my beloved great uncles. This specific connection to my family’s roots is why I spent most of my cherished “Guajiro Time” in Redención, a small town about 40 minutes north of Camagüey.

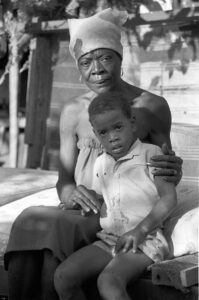

This series of portraits stands out because of the remarkable strength and dignity of this Afro-Cuban woman, whom I met during a day trip to Santiago de Las Vegas, near Havana. I initially asked her to sit for the photos you see here, but by the end, we had hit it off, and she asked me to take a portrait of her with her grandson.

Sadly, I was never able to send her the print, which I usually did for others by mail or through neighbors visiting Cuba on future trips. In the late ’90s, a Haitian-American painter saw one of the photos I exhibited of this woman and asked if she could use it to create a portrait painting based on this series.

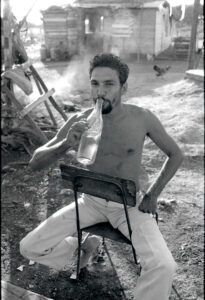

I played a harmless prank on this Guajiro, who you see here drinking homemade rum. In a video that has since gone missing, I used my large video camera, convincing him that it had unbelievable technology that could see through his skin and into his organs. I jokingly told him that what I saw inside was very concerning, which briefly scared him.

When I revealed the truth and showed him the video, he had a big, good-natured Cuban laugh—because that’s just how Guajiros roll. P.S. The out of focus chicken in the background ices this photo.

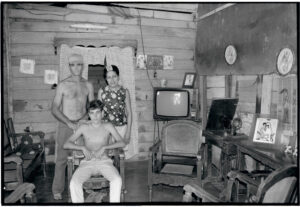

When I see this photo, I can’t help but feel I’m looking at an authentic, raw portrait of a loving Guajiro family. If you look closely, this isn’t just a portrait of the three people in the foreground but of five, possibly six, thanks to the wedding and birthday photos adorning the living room walls. The humility of this family is evident in the mother, photographed in hair curlers, and the husband and son, both shirtless and barefoot. These are the Guajiros I love so much!

My great-uncle Manolo, a Guajiro from Redención in Camagüey, gave me the most loving, illegal, and delicious meal experience I’ve ever had.

It was New Year’s Eve, 1993, and the occasion was a highly prohibited steak dinner from a freshly killed, government-owned cow under his care. To give you an idea of the severity of the crime, killing a cow in Cuba typically carries a 15-year sentence. Cubans often joke that it’s worse to kill a cow than a person. Despite the risk, Manolo was determined to give me and my ex-wife an unforgettable holiday meal, trusting that his neighbors wouldn’t find out or snitch if they did.

At the time, I didn’t fully grasp the magnitude of his rebellious act, but I knew it was more than just about eating steak—it was about defying a system in a country rich in agriculture, yet where meat was a rare luxury. Oddly, Manolo didn’t serve the steak with utensils. Instead, he urged us to tear the meat out with our hands, and to eat it like that, adding to the primal experience.

By the end, we were all covered in grease, our hands filthy, our faces shining with grease, grinning like satisfied pigs. We were completely out of our element, but that steak was incredible—and unforgettable, thanks to Manolo.

Throughout this book, you’ll find a series of portraits featuring couples, siblings, and friends. While you might think I asked to take these photos of people, more often than not, it was they who asked me. In most cases, it’s because they hoped I could consider printing and mailing the photos to them, which I often did. (These were the days before iPhones or digital images).

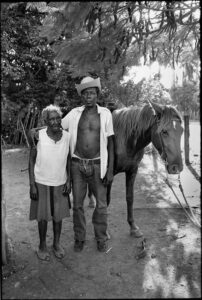

This particular photo was requested by a Guajiro from Redención who wanted a ‘good photo’ with his beloved mom and horse—the truest treasures of this Guajiro’s life.

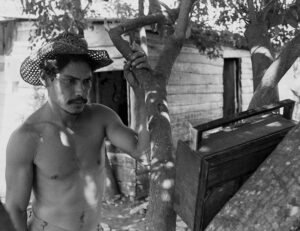

I think I felt most comfortable photographing Guajiros because, on my dad’s side, we were very much country folk. In contrast to city dwellers, I found Guajiros to be far more welcoming to me — the so-called ‘Miami kid walking around with strange cameras.’ The simplicity of life, naïveté, and gregarious nature of the Guajiros made me especially love spending time with my Guajiro family in Redención, Camagüey. I think the true grit and kindness of Cuba is strongest among the Guajiros.

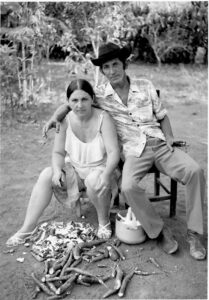

This photo captures a subtle, perhaps innocent, disconnect between a well-dressed, middle-aged Guajiro couple. On the left, the wife wields a knife, seemingly having just peeled numerous viandas, while on the right, her husband leans casually into her, holding a half-smoked cigarette. He’s not going to cook anything.

This is one of my top five favorite photos of all time, and certainly the best from my fourth and final trip to Cuba in the ‘90s. What makes the photo unique is the casual way these men are playing dominoes, while a freshly killed pig’s head sits trophy-like on the edge of the table.

I have no idea why the head was placed there, and I doubt it was meant as the prize for the game. But the presence of this single element elevates the image, making it one of the most striking photos you’ll ever see of people playing dominoes. At the very least, it’s the strangest, all thanks to the Guajiros of Cuba.

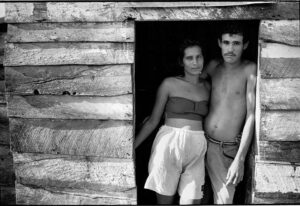

This young Guajiro couple from Redención, Cuba, in the province of Camagüey, were my photographic version of the American Gothic painting.

A few months after I revisited their neighborhood, they had split up. I don’t know if the challenges of living in Cuba were the reason, but throughout my time there, I found many couples frequently separating, even within the span of a year.

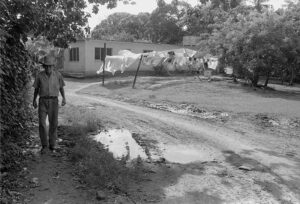

This old Guajiro, with his straw hat, walking in the breezy morning light of his country town, reminds me of my Guajiro grandfather Miguelito doing the same in Hialeah.

Old Cuban men in Hialeah, like my abuelo, often took these morning walks to buy fresh Cuban bread or small groceries like milk and eggs. In Redención, Cuba, I imagine this man was taking advantage of the cool morning to enjoy a stroll, perhaps on his way to visit friends or family.

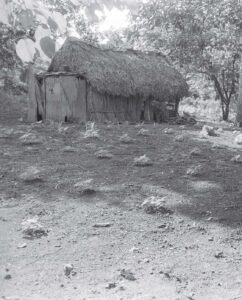

These bohíos—Cuba’s traditional countryside wood and straw homes—haven’t changed much since the ones seen in old Cuban paintings from the 1800s.

The main difference here is the modern touch: the TV antenna and the utility box for electricity on the front. Only recently did I notice that one of the owners appears to be watching me from their window.

This photo isn’t just about the decapitated pig or the headless Guajira holding the pot; it’s about the single drop of sweat rolling down her shoulder. That drop is the magical detail that echoes the intensity in the pig’s fierce stare.

Incidentally, this same pig head is featured as the trophy object in another one of my favorite ‘Surreal Cuba’ photo, which you can find at this link. In that context, the pig’s head takes on a completely different meaning.

Guajiros mostly want to be left alone to tend to their farms and animals. This makes them both a blessing and a challenge for the Revolution. Fiercely independent, Guajiros require a more courteous and collaborative approach from the government. They are generally granted some autonomy because they are unarmed, live in sparsely populated areas, and are crucial to meeting Cuba’s agricultural needs.

The downside for the Revolution is that Guajiros are hard to enlist for the kinds of repressive acts the government enforces in the cities. Political issues are often alien to their way of life, and such actions go against their code of honor.

As Guajiro children grow into their early teens, many families face a difficult decision: stay in the countryside and continue farming, or move to the city for better educational and professional opportunities. This dilemma is common worldwide, including in the United States, but for Cuba’s Guajiros, it’s especially bittersweet. Staying in the countryside offers more autonomy from the prying Socialist government and is often safer for their families.

One of my favorite great uncles, Luis from Redención, suffered the consequences of this choice. He moved to the city, but tragically, his beloved grandson was murdered at a discotheque in Camagüey. The pain of that loss haunted my uncle for the rest of his life. Yet, it was this move to Camagüey that enabled his daughter to become a professional, marry, and ultimately give birth to the grandson he cherished and later lost.

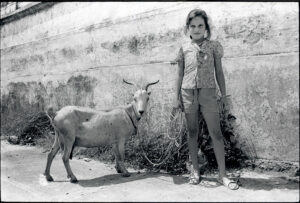

This Guajirito may seem morbid, smiling as he holds the lifeless body of a goat, but in reality, he’s holding it just before it’s hoisted onto a pole to dry. Later that night, this boy and his family would enjoy the goat as part of their New Year’s meal to welcome 1994.

The accompanying photo here is part of an unusual family snapshot that didn’t make it into the photo book.

It wasn’t until I went to Cuba that I realized how smart pigs are. I had no idea they could be as intelligent, loving, and obedient as man’s best friend—like this one here with his Guajiro master. On one of my first days in Cuba, I met a beautiful pet pig who lived next door to my cousin in the city. My cousin and I spent an hour with him, as his owners proudly showed how well-trained and obedient he was.

The next morning, I was jolted awake by the sound of the same pig screaming for its life. My cousin explained that the family had planned to slaughter the pig once it reached the perfect weight, and that moment had come. From then on, every pig I saw in Cuba—including this one—felt like a creature with its days numbered, even if it seemed like part of someone’s family. That’s a pig’s main problem: Cubans love to eat pork.

Even though many homes in the countryside may be close to one another, they are not all equal. Some have TVs and are built mostly of concrete, while others are not as developed. Some homes have better access to drinking water or irrigation.

What’s special about the Guajiros, however, is that they don’t need government programs to force them to collaborate with each other. The Guajiro way of life is inherently about helping one another, regardless of differences in what one household has compared to the other.

The cycle of life in the Cuban countryside is straightforward. Guajiros are allowed to keep a portion of what they raise to sustain themselves and their families. This applies to animals as well, except for cows, which are strictly government-owned and carefully monitored, even though farmers are responsible for raising them.

The one animal you can always count on being sacrificed by Guajiros—whether on a weekday or weekend—is the pig. Pigs are plentiful, multiply easily, and are deeply embedded in Cuban food culture.

Dealing with machismo is a fact of life for most Guajiras but when it comes to doing all but the heaviest of labor, there is little difference between the workload of men and women. The Guajira mentality is simple: food must be provided, and animals and crops must be tended to daily, period.

Perhaps the biggest challenge Guajiras face is living with husbands who drink too much. Anecdotally, and unsurprisingly, alcohol is one of the leading causes of problems in Guajiro households in the countryside.

If I had taken this photo in the ’70s, it could easily be mistaken for a scene from the farmlands of western Miami. This Guajira country woman reminded me of my grandfather Miguelito—a proud Guajiro himself. Even though life moved him to the city life of Hialeah, he never let go of his country roots. Every single day, one of us in the family had to drive him out to tend his chickens and pigs on a small farm he rented.

This photo of a wooden frame house transported me straight back to my early childhood. And this woman—on a calm Saturday in Redención, Cuba—felt just like one of those Guajiras who might’ve been cutting the same vegetables in Hialeah, keeping traditions alive on both sides of the sea.

Look closely at the swing, and you’ll see it’s held up by unevenly tied knots—a small, quiet detail in this countryside portrait of a young Guajira. With her freckled face and innocent gaze, she radiates a kind of delicate honesty. It’s as if she’s saying, take your photo and go, because in that swing—surrounded by the familiar—she is already home.

Cuba has formed or influenced more musical styles than any other country in the world, and that deep cultural tradition is evident throughout the island. Whether as a tonic for life or simply for the joy it brings, the tradition of music lives inside every Cuban from birth.

If you put this charismatic Guajira’s photo alongside the other Guajiro pictures in this book, you’ll notice one major pattern: they all look strong and healthy. This is particularly notable because I took these photos during Cuba’s Special Period, right after the fall of the Soviet Union, when many city-dwelling Cubans were protesting severe food and power shortages.

In my own family, I saw a stark contrast between those who lived in the countryside and those in the cities. My Guajiro relatives never lacked food, while my cousins, aunts, and uncles from the cities often remarked how the Special Period forced them to lose 20, 30, even 40 pounds.

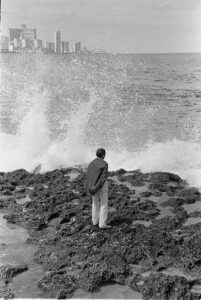

This photo was the runner-up to be the cover image of Surreal Cuba, largely because of its intriguing backstory and its symbolic twin image in Miami.

I call this photo El Añoro (The Yearning). I was cruising along Havana’s famed Malecón when I spotted this man, standing stoically before the towering, crashing waves you see here. My camera wasn’t nearby, and I didn’t think I’d have enough time to capture the moment. But whatever held this man’s gaze kept him rooted in place, allowing me to snap the photo. For more than five minutes, he stood completely still, unfazed by the waves crashing around him.

Years later, while going through my late grandmother Micaela’s photos, I found a counterpart to El Añoro. The Polaroid shows my grandmother contemplating the waters off Key Biscayne in Miami. Although I wasn’t there when it was taken, I’m certain she was thinking of Cuba. The ocean always reminded her of home.

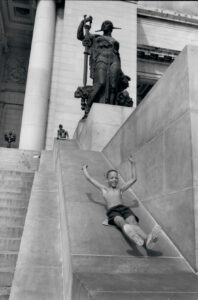

This carefree boy is sliding down the front wall of Havana’s gorgeous Capitolio Nacional building, which is a gorgeous smaller replicate of the U.S. Capitol building. Even though it was constructed to house the Cuban Congress before the Revolution, after Congress was dissolved with the Revolution, the building ceased its legislative function.

Today, El Capitolio is mostly a major tourist attraction that serves as the home of the Cuban Academy of Sciences and houses the offices of the National Assembly of People’s Power, which is Cuba’s legislative body.

I like the fact the building is not used for governing Cuba because it gives me hope that one day the Capitolio could play a symbolic home in the restoration of a democratic government in Cuba.

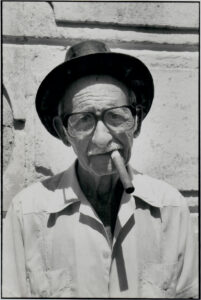

I’ve never displayed this photo before because, even though tobacco is an intrinsic cultural part of my Cuban heritage, I’ve personally never wanted to promote anything about the industry. That said, I can’t deny that the brilliant light on this man’s gaze with his cigar, glasses, white linen shirt, and the wall behind him make for a classic photo that is as Cuban as any I’ve ever taken.

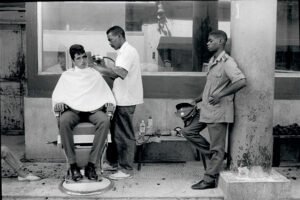

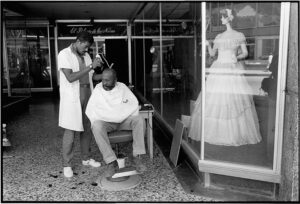

Even though I shot thousands of photos of throughout Cuba, I rarely photographed police officers or soldiers because I never wanted to trigger suspicions about me. I don’t know how I mustered the courage to take this photo of this sidewalk barbershop but it is one of my favorites because when you examine it closely, the photo reveals interesting details such as how one soldier is holding his friend’s hat so the other one can get a haircut.

After baseball and boxing, the next favorite national sport of Cubans is arguing. We Cubans debate about everything, and we do it so loudly and passionately that it often makes others think we’re fighting—even when it’s just a heated discussion.

I don’t know what these men were forcefully debating that day at Havana’s national zoo, but I love the metaphor the garbage can adds to the photo.

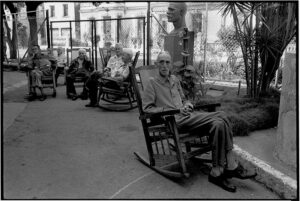

Like most Latinos, Cubans value their elders. Unfortunately, the Castro brothers took this to an extreme. Through their iron grip on power, they turned it into a twisted game, driving Cuba’s youth into exile and stripping the island of its vitality—its potential for population growth, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship.

Much like the old men pictured here in Havana, Cuba’s leadership consists of a geriatric circle clinging to power at all costs, refusing to step aside even as the country stagnates.

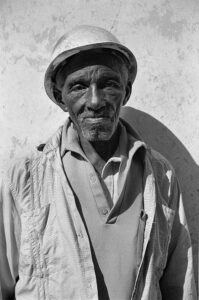

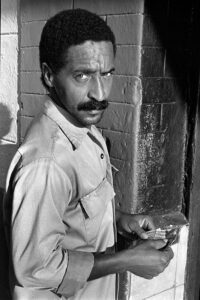

Construction Worker The eyes of this construction worker, whom I photographed in Camagüey, offer a true window into his soul. This photo speaks to me of someone who is quiet, kind, and earnest. His gaze has pierced my heart so deeply that he became the physical inspiration for Echauri Suarez, the fictional main character of Bistec, the film script I adapted into last summer’s hugely popular podcast series.

There are some photos you can never plan because they are so incredibly unexpected. Such is the case with this image of my distant teenage cousin, Anaisa, who stands with quiet grace, holding her black comb in front of a horribly warped mirror that refuses to reflect her youthful beauty.

The large oxygen tank to the side adds an ominous detail to the scene. I have exhibited this photo several times, and in 1994 it earned Second Place nationally in Portraiture from Popular Photography Magazine. The coolest part of all is that I took this shot in my dad’s former bedroom in his old home in Cienfuegos.

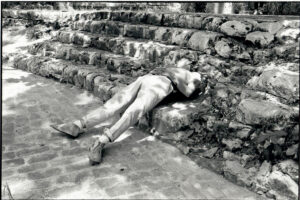

I was probably around the same age as this young man when I quietly took his photo inside Havana’s storied Parque Almendares.

It was one of the first photos I snapped in Cuba, and it stands out to me because this unusual nap either shows that he knew how to truly relax or that he was simply too bored to care what people who stumbled upon him in public might think.

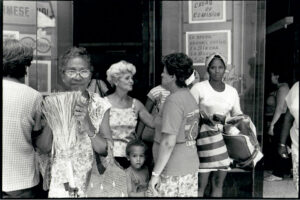

This chaotic street scene, with 10 people, features three main protagonists, each raising different questions about what’s really happening here. First, there’s the older woman holding a brand-new broom, her pose both optimistic and tentative.

Then, there’s the small child who has stumbled into the photographer, uncertain and perhaps curious. Finally, there’s an Afro-Cuban woman, who may have just had her hair done, casting a mildly curious glance at what the photographer is up to.

The slow rhythm of bike traffic and this shirtless man surveying his neighborhood’s morning bustle inspired the opening scene of my film and podcast series, Bistec. People on second-floor balconies often seem to have endless time to observe the turtle-paced flow of daily life in Cuba. But for some—especially the neighborhood minders—it’s also the perfect vantage point to quietly watch and report for the state.

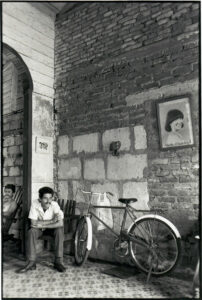

Before my first trip to Cuba in 1993, I studied the Great Depression era work of photographer Walker Evans and I purposed that, in addition to capturing Cuba’s propaganda, I would focus my lens on the common and the everyday. This bike, baking under the blazing sun of Camagüey, became one of my favorites.

I can’t imagine who could have touched a bike exposed to that much heat.

I found this very old, rustic brick kitchen in Havana fascinating and continue to marvel at how emblematic it is of Cubans’ ability to preserve all sorts of things so they last forever.

As I walked throughout Cuba, I was always searching for photo gems like this one.

Interestingly, the owner of this kitchen assured me they didn’t use it much anymore, but the clean pots and pans you see here suggest otherwise—it may be more frequent than they care to admit.

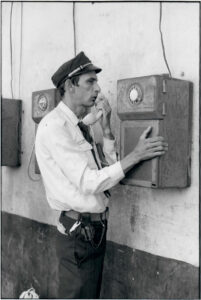

I haven’t been back to this spot in Havana since I took this photo 31 years ago—but honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if this phone is still there… and still working.

Here’s why: Cuba is a dictatorship, and in a totalitarian state, easily accessible technology that isn’t fully controlled is viewed as a threat. That’s why mobile phones—even today—aren’t as widespread as you’d expect. And it’s also why this desolate, grimy old phone booth is likely still standing, still functional. In a country where modern tech is seen as dangerous, the past gets propped up—not because it works better, but because it can be controlled.

March 8, 1994—International Women’s Day, as the poster says—is a date forever etched in my memory. That was the day I found myself detained in a Cuban police station alongside two teenage prostitutes and two middle-aged Spaniards.

The trouble began outside a travel agency in Old Havana. As the group exited the building, I snapped a photo—paparazzi style—of the men walking out with the girls. It was a foolish decision, driven by a surge of outrage. I felt these men were exploiting the young women, and my camera became my way of calling it out.

Unfortunately, the moment turned quickly. They confronted me, demanded the film, and when I refused to hand it over, things escalated. The police got involved, and we were all taken to a station on the Malecón.

To keep a long story short, the men accused me of following them from the airport with the intention of harming them—and trying to hurt Cuba. It turned out they were hotel investors. I was the only one left behind for a full investigation, which lasted the entire day.

What followed was intense: threats of violence when I insisted on my rights as an American, hours of questioning, and the slow realization that I had stepped into a far more complicated reality than I understood. That day taught me hard, invaluable lessons about power, perception, and life in Cuba.

The middle finger flashed by the woman in this poster is a kind of poetic justice—a perfect symbol for the chaos and defiance that marked March 8, 1994, for me.

I ran into this construction worker on the streets of Camagüey and have always been struck by the quiet power of this moment. There’s something about the contrast between his stance and the layered backdrop of old buildings, tangled light poles, and the clouded sky above that still fascinates me.

This family bicycle ride makes for uncomfortable viewing as the apparent father in this photo looks gassed while the toddler is passed out, and her mom calmly holds her.

The biggest question I have is a safety one. How did they stop this bike without dropping the passengers it wasn’t made to carry?

The fact the dad has a bandaid on his left forehead is concerning.

Photography doesn’t always need to be in focus. In fact, this book was supposed to include another out-of-focus photo like this one, but I couldn’t find it. When I do, I’ll include it, because even though it’s technically inferior to this one—and perhaps even a bit boring—the other photo reveals a crucial part of the craziest backstory this book has to offer.

Hurray for blurry birthday photos of kids being pulled in a cart by a goat and his handler.

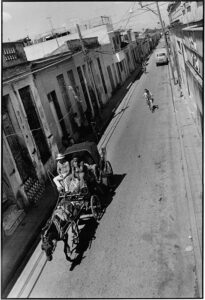

This photograph holds a special place in my life because it won a first-place prize at an exhibition and was the first photo I ever sold to a collector. What makes the image unique is its slight tilt and how the horse and buggy with a pensive passenger interact with the stark, sunlit scene in Camagüey, converging with cars, trucks, bikes, and people.

This colossal papier-mâché figure of Gulliver, from Gulliver’s Trail, was a photographic find on a side street in Trinidad, one of Cuba’s best-preserved colonial cities. Even in its state of disrepair, the art piece was impressive—a remnant of a fair that Trinidad had celebrated just a few months earlier.

What intrigued me wasn’t just the scale of the parade float, but also the way Gulliver was depicted in a slumped pose of defeat, an apt metaphor for the prospects of youth in Cuba—though perhaps that was only my interpretation.

When you press the camera shutter thousands of times across hundreds of rolls of film, you occasionally stumble upon accidental gems. That’s exactly what happened here. Without meaning to, I captured the innocent eyes of a beautiful little girl in the foreground, while in the background, a boy was caught mid-action, trying to spit out a piece of gum.

Everyone insists I meant to take this shot, but the truth is, even the most talented photographers get lucky sometimes—just like I did here. P.S. I took this photo inside my father’s former childhood home in Cienfuegos, and this is the fourth one I included in my main collection that came from there.

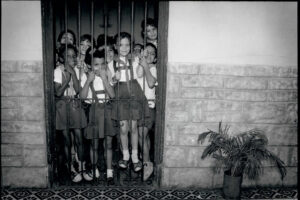

Walking around Cuba with various cameras and large lenses made me a very visible target. Sometimes, it caused people to shy away from where I was photographing, but many other times, it sparked curiosity—or even spontaneous celebrations, like the one I elicited from the Pioneer school children pictured here. The thought that many of these kids would now be in their 40s is simply mind-blowing.

I love the innocence of these three boys pointing their toy guns at me. Ironically, this photo perfectly captures the cat-and-mouse games between Cuba and the United States. Strangely, I do believe the Cuban government would love to genuinely convince everyone that the U.S. is hurting them, but no one buys it.

This love/hate, yin/yang dynamic is why I say Cuba lives with a strange dichotomy—on one hand, the Castro government despises the U.S., but on the other, they need us economically.

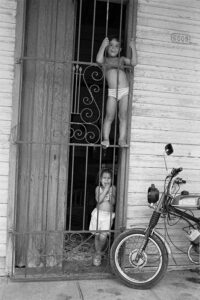

This tall wrought iron window was a signature architectural feature of my late father’s childhood wood-frame home in Cienfuegos. Knowing how rambunctious he must have been as the youngest of four siblings, I can’t help but imagine this playful boy and his sister monkeying around on that window just like my dad and aunt would have done decades earlier.

The beauty of taking this and other photos over 30 years ago is that it leaves you wondering what became of your subjects. That’s the case with this single mother, who I imagine is probably around 60 today, and this boy, who would be nearing his 40s.

I know that almost everyone I photographed over the age of 60 has passed away, and many of the children, like this one, went on to become professionals—doctors, teachers, and more, both in Cuba and abroad. Where Are They Now sounds like the perfect idea for a future digital chapter to this Surreal Cuba book.

There are many crazy stories of Cuban exiles who when retracing their Cuban roots discover that their former family homes have been converted into government housing, restaurants, schools, government offices, and even funeral homes.

In my case, my dad’s humble childhood home in Cienfuegos was not fancy enough to be turned into anything big so my distant cousins who still occupied it turned it into a neighborhood Fix-a-Flat-Tire by day, and home by night. The Ponchera, as Cubans call it, was the place to go for any flat relating to a car, motorcycle, or bike.

These twin sisters were my dad’s beloved, longtime neighbors from Cienfuegos. My dad was thrilled I found them because he said they were masters at treating him as a boy to his favorite food, black beans and white rice.

When I met them, they told me they regretted not getting married because they made a pact that they would put their mom before their personal interests. To the end, they would only have each other.

I don’t remember if this guy was feeling suspicious of me and my cameras, but many others occasionally treated me with paranoia or outright rejection when I tried to photograph them. I didn’t blame anyone for feeling that way, and I generally found it harder to get people in the city to cooperate than those in the countryside.

My approach was to purposely look like a loud and proud foreign tourist—carrying bulky camera equipment and wearing tacky t-shirts—so no one would think I was some kind of undercover anti-Cuba plant. With one rare, massive exception in March of 1994, this strategy worked.

I will never understand how this woman, selling mostly useless trinkets and fake rings from her Havana home’s windowsill, ever made ends meet. The truth is, for most Cubans, if they don’t have family in exile or good friends from foreign countries who truly care about them, life can be extraordinarily difficult.

In the early ’90s, when nearly any all forms of entrepreneurship were illegal, people either resorted to the black market or struggled like this woman. Incidentally, what I find most intriguing about this photo are the two honey bear bottles and the fake hand.

I’ve seen people get haircuts in all sorts of places, but this one takes the cake. It’s the only time I’ve ever seen a barber cutting a man’s hair in front of a quinceañera and bridal store. If you look closely, you’ll notice not only that the barber is dressed formally, but that he’s also using electric clippers.

There must be something special about getting your hair cut in a place called El Palacio de las Novias—The Bridal Palace.

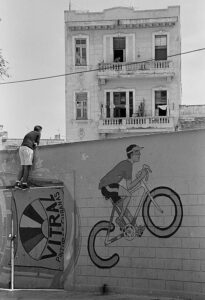

«Bicycles—particularly Chinese-made ones—are treasured in Cuba, as they are the most common mode of transport after public transportation. In a country grappling with spiraling fuel costs, bikes offer Cubans a way to stay active, reduce fuel consumption, and save money.

The biggest drawback? When Cuba is bombarded with rain, as it often is, riding a bike becomes far less appealing.

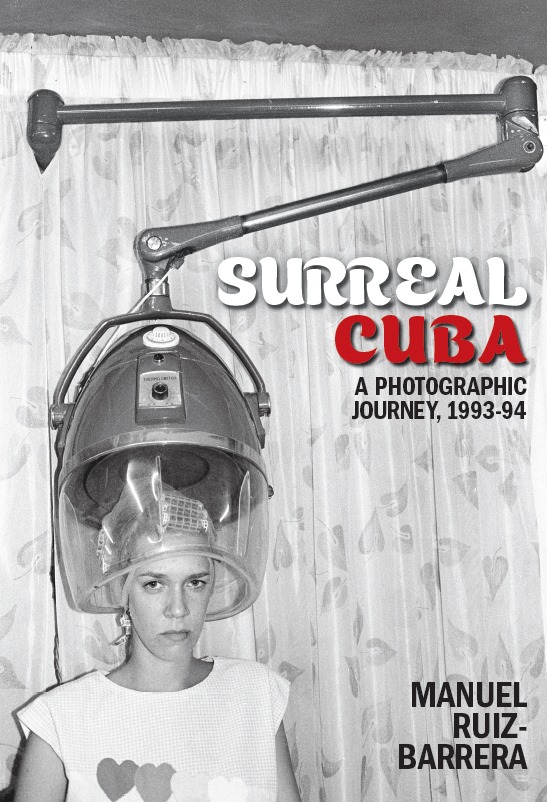

This bulky, retro hairdryer atop this woman’s head has always been one of my favorite images because it serves as a metaphor for the surreal, dystopian world I encountered in Cuba. That’s why I chose it as the cover image for this book, and why it became the postcard invitation for my first solo photography exhibit at Florida International University in 1994.

The photo reminds me of one of the most unusual things I enjoyed doing in Cuba: watching the Communist island’s carefully orchestrated newscasts. These broadcasts showed the world in constant turmoil, from wars and riots to worker strikes, famine, and protests. In contrast, whenever Cuba was mentioned, it was depicted as orderly, hardworking, and collaborative. The message these newscasts hammered home daily was that while the world burned, Cuba stood as a pillar of peace, happiness, and solutions.

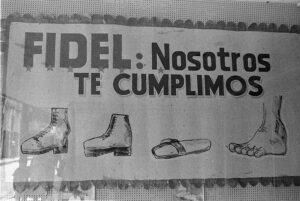

I suspect whoever constructed this wonderfully ironic poster either got seriously rebuked or found themselves in deep trouble. That was my immediate reaction upon stumbling across this masterpiece of Cuban surrealism outside a downtown Camagüey shoe store.

I took this photo in September 1993—though not very artistically—and hoped I could capture it again when I returned in December of that year. Unsurprisingly, the poster had been removed—perhaps along with someone’s job, or worse.

Even Cubans who aren’t officially snooping on others still do. That’s because in Cuba, everyone is either snooping or watching to make sure no one’s snooping on them. I know—it’s exhausting, which is exactly the point.

This culture of paranoia, Cubans vs. Cubans, is best summed up by a popular and widely shared saying that I’m convinced was planted by the Castro brothers themselves: ‘For every two Cubans, one is a snitch.’ Simply believing that saying is a powerful deterrent to anyone who even TRIES to think or speak against Castro’s dogma.

P.S. I love this guy’s Converse sneakers.

This photo serves as a metaphor for how complicated and entangled life is in Cuba, where the system practically encourages everyone to know everything about each other. The reason for this entanglement is that it’s an effective way to keep tabs on those who don’t conform perfectly.

The aerial shot of this man feels a bit sinister, as it implies that, unbeknownst to him, someone bigger is always watching.

Yes, you’re seeing this photo correctly. This man, a bus driver, is speaking directly into the headset instead of the speaker part of a public phone—and strange as it seems, it worked.

A friend who recently saw this photo marveled that she remembers when these phone booths were still in Havana, though, like the phonebooths in the U.S., they no longer exist.

To understand the true secret behind the Castro Family’s 65-year—and counting—dominance, you need to understand the nuclear the government gets from its Comités de Defensa de la Revolución (CDR) apparatus. These neighborhood watch-style organizations operate in every community across Cuba, gathering intelligence and mobilizing patriotic citizens against degenerate citizens for the ‘Fatherland.’ Fidel Castro himself called the CDRs, ‘the Vanguard of the Revolution.’ There’s even a national museum in Havana dedicated to the CDRs, which we exclusively recorded in 2024 and you can watch here.

When people speak of the Castro dictatorship dynasty they often focus on them, or the police or military apparatus but the real pervasive power of the regime lies in its ability to micro-target repression against people through the CDRs. This insight into Cuba’s dystopian society is what drove me to write and produce, the popular ‘BISTEC’ Podcast Series that you can listen to on YouTube, Spotify, and all digital platforms. ‘BISTEC’ is the first story that has ever delved deeply into the crazy world of Cuba’s vigilance society, and you can find it everywhere by simply searching for “Bistec” and “Podcast.”

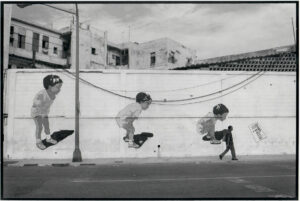

In Havana, and across Cuba, elaborate public murals serve as constant reminders that the State is always watching. The mural pictured here drives this point home, showing that from a young age, every Cuban is expected to be loyal to the Fatherland. The mural’s final words read, ‘Always with the Fatherland.’ This message of unwavering loyalty to the Revolution is pervasive and creatively reinforced daily through all forms of media, including TV, radio, film, and the arts.

Fidel Castro took a page from Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, who famously said, ‘If you repeat a lie enough, they will believe it.’ In Cuba, it’s not that everybody believes it anymore so much as it is that everyone knows you defy the Group Think at your own peril.

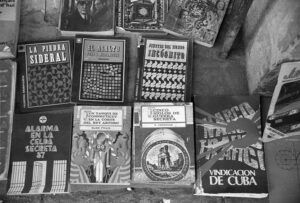

When you browse any book flea market or dealer in Cuba, you’ll quickly notice that political thrillers and biographies dominate the shelves. It’s no coincidence—the government loves to fuel anti-Yankee conspiracies with spy books, and paranoia plays a key role in justifying the suppression of opposition voices or groups.

If you’re ever curious why so many Cubans seem obsessed with conspiracy theories in the U.S., let’s just say many of us got our practice in Cuba.

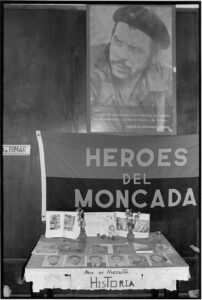

Next to Fidel, the most prominent figure plastered on Cuban murals, signs, and in pop culture is the late revolutionary hero Che Guevara. The myth of the dashing Argentine, killed by the CIA while trying to ignite guerrilla wars in Bolivia in 1967, has only grown stronger. His execution while still young and at the height of his charismatic powers immortalized him as a revolutionary icon. Fidel was known for expertly cultivating the brand of martyrs, and none shine brighter for the Revolution than Che.

Many tourists visiting Cuba buy Che gear—like t-shirts and posters—as if collecting fashionable souvenirs. Some even tattoo Che’s image on their arms or chest. Hollywood has further fueled the cult of Saint Che with big-budget films like The Motorcycle Diaries and Che, adding to the legend.

I knew instantly when I took this photo that it would become one of the iconic images from my trips to Cuba. All I remember is walking past a classroom with my camera, and what started with a few kids near the front posing for the photo quickly turned into the entire class clamoring to be part of the shot. The irony of this photo, both then and now, is what makes it stand out.

It captures the paradox of Cuba’s Socialist schools: while they produce highly educated children, those same children are ultimately prevented from reaching their full potential by the very system that educated them. Fidel Castro had a saying for this, and it’s not encouraging for anyone who doesn’t devote their life solely to the Revolution: ‘Dentro de la Revolución, todo; fuera de la Revolución, nada.’ This translates to: ‘Within the Revolution, everything; outside the Revolution, nothing.’

The first, and almost only, home I stayed in while in Havana belonged to this woman, Mercedes. I loved Mercedes and felt a special connection to her house, located in the Santo Suárez neighborhood, with its historic charm, impeccably kept mosaic floors, and ornate wrought iron windows. Despite being the president of her neighborhood’s CDR and a lifelong Revolutionary, I always felt protected by her and her family, who became my Havana family during those years. Ironically—and I can’t be certain of this—I think the fact that I stayed with her so often served as proof to the government minders investigating me that perhaps my activities were more innocent than their always-suspicious minds might have believed.

Most of us have heard about Cuba’s passionate preservation of 1950s American cars. Thanks to Cuban ingenuity, these classic vehicles are still running 70+ years later and can be seen clustered around Havana. Personally, if I could have a photographic do-over of my journeys, I’d skip the cars and head to the beauty salons to capture all the antique hairdryers—like this one.

This old man, clearly bored and likely retired, was on duty as the neighborhood night watchman in this stale, bare room. Four details stand out in this image: the ‘Do Not Smoke’ sign, the expression on his face, the fan he’s holding, and the awkwardly placed shoe on the desk cabinet. In countless public institutions or museums across Cuba, it’s common to find workers with expressions of utter boredom.

It’s ironic that in a country constantly speaking of economic hardship, a significant portion of its budget is allocated to the military. In this photo, taken at ExpoCuba—a large permanent exhibition space showcasing Cuba’s economic and scientific achievements—the vital role of the military in society is emphasized by these two mannequins standing next to a cutout of Fidel.

His quote reads, ‘Without Revolution, there is no true independence, and without Socialism, there is no Revolution.’

If you could interview Fidel’s corpse today and ask him which battle he was most proud of winning, I suspect he’d point to the 1961 U.S. military debacle at the Bay of Pigs, known in Cuba as the Batalla de Playa Girón. This three-day invasion, which was greenlit and then halted mid-battle by President Kennedy, became a massive national and international PR victory for Castro.

Girón catapulted Fidel’s status as a Revolutionary Badass who had defeated the U.S. and gave him the justification to fully align Cuba with the Soviet Union. For the rest of his life, and still to this day, Cuba continues to immortalize the victory at Girón.

This political mural translates to ‘No One Here is Gonna Surrender, Dammit!’ It was strategically placed on a road leading to José Martí International Airport, just a short distance away. The mural’s proximity to the airport isn’t lost on me—I see it as the Cuban government’s way of reminding both visitors and citizens that the Revolution’s grip on power is unyielding and ‘eternal,’ making any thought of change seem futile.